The Doctor’s Wife

by Deidra Jackson

A practicing psychoanalyst and his son, a literary scholar, posit a radical theory: that Sigmund Freud’s wife may have influenced her husband’s work more than anyone cares to admit

M

artha Freud, who for more than 50 years was married to one of the 20th century’s greatest thinkers, remains mysterious to the world, scientific or otherwise. Despite her long marriage to Sigmund Freud, history ignores her by discounting her importance and avoiding much discussion of her in any Freud biography or psychological study.

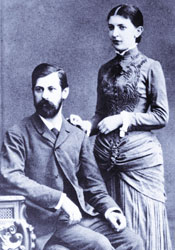

Sigmund and Martha Freud were married more than 50 years, but little attention has been given to her contributions to his landmark theories of psychoanalysis.

But could Martha—who raised the Freuds’ six children while Sigmund worked as many as 18 hours a day—logically be involved in such an enduring relationship without directly influencing her husband’s profound psychological concepts?

Hardly, say UM English professor David Galef and his father, New York psychoanalyst Harold Galef. They contend that Martha had an impact on her husband’s psychoanalytic work by influencing his behavior and thinking. The Galefs are co-authors of “Freud’s Wife,” a provocative joint paper recently published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry. More than 50 years after Martha Freud’s death, they report their intriguing findings in 20 pages of the prestigious journal.

“Most biographies of Freud and psychoanalytic studies treat her as an early romantic interest and neglect her once she becomes a wife and mother,” the Galefs assert in their study. “Still, if Freud’s theories on everything from domesticity to sexuality were drawn partly from his own experience, Martha’s personality and her interaction with her husband are significant to the history of psychoanalysis.”

Harold Galef, a psychoanalyst for 40 years, said he and his son were interested in whether Freud, who has been criticized for his psychoanalytic treatment of women, had been influenced by Martha.

“We wondered if it was just a quirk of the culture of that time that a woman who had an interesting background suddenly disappeared.”

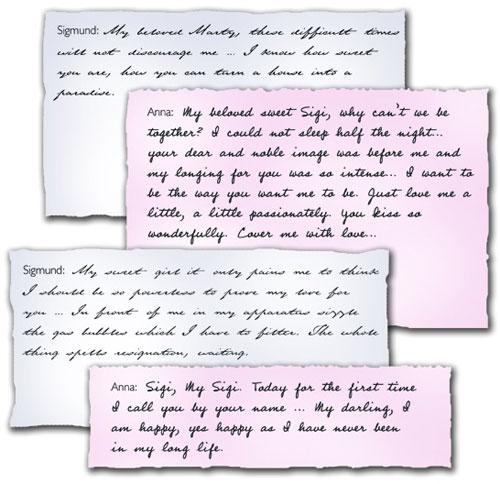

Letters between the couple provide a revealing glimpse into Sigmund Freud’s personality

In biographies that mention her briefly, Martha emerges as a domineering parent and efficient spouse who employed as many as six domestic staff and managed a strict household. The portrait that emerges is of Martha’s preferring an acquiescent, subservient role as the spotlight shone on her brilliant husband’s increasingly successful scientific career.

“While Freud attempted to impose system on the mental derangement in his patients’ lives, Martha brought order to the domestic sphere,” the Galefs write. “To analogize: Freud collected antique statuettes for his office, and Martha arranged them.”

But in the course of the authors’ focused examination, Martha is revealed as intensely competent, “an avid reader who knew the German classics and some world literature,” and appealing to Sigmund as a proven source of calm and security “beyond the initial romance.” Born into an affluent family, which included a respected religious leader and university professors, Martha, despite how she presented herself, was sophisticated.

“She’s a vivacious young woman up until the end of her independent life,” Harold Galef says.

Although Harold and David Galef discount any implications that Martha was actively collaborating with her husband to develop psychoanalytic theories or engaging in similar research, they suggest she substantially affected his thinking.

“In her child-rearing practices and own feelings toward sex, femininity and marriage, she clearly gave her husband patterns from which to build theories about women,” David Galef says.

As the Galefs argue in their findings, echoing a belief with which Freud followers would agree, “Certainly Freud used his family as the basis to build his theoretical underpinnings of psychoanalysis.” But the authors write, “Is it not unreasonable to assume that Sigmund Freud would use his multifaceted wife, Martha, ‘as a template upon which he based some of his theories about female behavior?’”

Dr. Jules Glenn, a Great Neck, N.Y.-based psychoanalyst for 50 years before he retired in February, praised the Galefs’ work as research “presented in a very clear way with very good evidence to support their propositions.” “It’s very, very interesting,” says Glenn, whose research has been published in journals worldwide. “Even though Martha Freud was an important person in Sigmund Freud’s life, nobody has really bothered to look into her life to see what she was like. From ‘Freud’s Wife’ you get a very good picture of the kind of person she was.”

Joseph Urgo, chair of the Department of English, says, “By examining Freud’s own very specific relationship to one woman, we may have cause to think again about the origins of his influential generalizations about women, men and sexuality.”

David Galef—author of more than 70 short stories and numerous published books of fiction, nonfiction and poetry—was inspired to delve into Martha’s life after attending a Freud exhibit that focused on the noted neurologist’s career. Featured in the displays were innocuous pictures of Sigmund in his office, with his daughter and frolicking with his dog, but almost no pictures of his spouse.

“I thought, ‘What about Martha?’” David Galef says. “Who’s ever talked about her?”

So the three-year inquest began. Harold and David Galef carefully scrutinized biographies of Freud, where they found Martha mentioned mainly in reference to the couple’s four-year courtship (1882-1886), when the two exchanged some 1,500 letters and collaborated on a secret diary. The Galefs examined published untranslated letters from such resources as Sigmund’s work, biographies and other books, and analyzed a charming cache of unpublished, untranslated letters at the Freud Archives in the Library of Congress.

Martha clearly gave her husband patterns from which to build theories about women.

David Galef

The extensive collection, which Harold Galef describes as “four years of hectic correspondence,” is an intriguing assortment of letters the couple exchanged almost daily during their engagement. The letters, which are written in German and remain mostly unpublished, provide a revealing glimpse into Sigmund’s personality and offer insight into the development of his thoughts when he was striving to establish a scientific career. It was through personal correspondence that he often described his research to Martha.

But what do the letters reveal about Martha? They reveal her posing as “a foolish girl to be educated by Dr. Freud,” the Galefs say.

Martha writes,“I finally have read your postcard with Max’s help because it was difficult to read. Yes, that’s how stupid your dear girl is.”

In another communication less than one week before their engagement, Martha, again, assumes a submissive role. She writes about a cake she is sending to “Sigi, mein Sigi,” as the Galefs surmise, “a love tribute for Freud, the scientist, to dissect. She confesses that she really wanted to send him poetry, but her muse is mute and she has little time; hence, she will stick to the simple prose of reality.”

During the course of their four-year courtship, the letters reveal Sigmund to be a darkly romantic figure, a jealous and obsessive suitor, desirous of continuous attention.

“Oh, how wonderful it is going to be,” he wrote to Martha in June 1885. “... we will marry soon and I will cure all the incurable nervous patients and you will keep me well and I will kiss you till you are merry and happy—and they lived happily ever after.”

“The truth, as psychoanalysis teaches, was somewhat more complicated,” the Galefs write. “In a patient, Freud might have regarded it as an omission, if not actual complicity.”

Sigmund, who refined the concepts of the unconscious, contributed to science a therapy for the understanding of psychological development and the treatment of abnormal mental conditions. The authors’ assertions that Martha inspired Sigmund’s psychoanalytic theories have been met with cynicism from some diehard Freudians. Moreover, the authors faced resistance from some Freud archivists reluctant to allow outsiders to view unpublished resources.

“When we submitted the work, we received some readers’ reports that positively bridled at our bringing up Martha in this connection,” David Galef says. “Freudians tend to view this kind of revision as an attack on their idol, as insinuating that Freud wasn’t responsible for all his own work. We’re not suggesting that, though in fact, no one lives in a social vacuum.”

For many years, Sigmund—whose revolutionary theories continue to permeate undergraduate and graduate psychology courses, as well as many other disciplines—has enjoyed a following from supporters who hail him as a genius and a scholar of the human mind, but receives rebuffs from detractors who argue that his theories remain in place simply because they can’t be proven wrong.

“Anything said that is less than congratulatory about Freud is considered an attack of his work,” Harold Galef says. “We hoped to learn more about Martha Freud as an individual, and not just as a good Viennese housewife.”

Harold and David Galef also collaborated on a psychoanalytic study of camp aesthetics, which won a prize for the year’s best essay in Studies in Popular Culture.

The authors believe that their research will help shed light on the preconditions of Freud’s theories. Regardless of the obstacles, they were buoyed by the significant, but scant, revelations that support their assertions.

“So many of Freud’s precepts are deemed universal, but are, in fact, the product of late 19th century Vienna, living with Martha and so on,” David Galef says. “Discovering the dynamic between Martha and Sigmund and what enabled them to function together was intriguing. It’s true, the spouses of most famous people tend to be neglected, but that’s a distortion. You can’t live with someone for years and not have an impact.”

Sigmund and Martha Freud were married more than 50 years, but little attention has been given to her contributions to his landmark theories of psychoanalysis.

Sigmund and Martha Freud were married more than 50 years, but little attention has been given to her contributions to his landmark theories of psychoanalysis.