Aerial images of Long Beach taken before and after Katrina illustrate the scope of the storm’s destruction. The top image, from 2004, is from the National Agricultural Imagery Program; the bottom is from a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration aerial photography project only days after the hurricane’s landfall.

Aerial images of Long Beach taken before and after Katrina illustrate the scope of the storm’s destruction. The top image, from 2004, is from the National Agricultural Imagery Program; the bottom is from a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration aerial photography project only days after the hurricane’s landfall.

Before and after images of Point Cadet show widespread damage to homes, commercial buildings, vegetation and infrastructure. The left photo is a QuickBird image taken months before the storm; the right is a NOAA aerial photo shot shortly after the disaster.

Before and after images of Point Cadet show widespread damage to homes, commercial buildings, vegetation and infrastructure. The left photo is a QuickBird image taken months before the storm; the right is a NOAA aerial photo shot shortly after the disaster.

Months later, their work continues, now in the cleanup phase.

Civil engineering professor Chris Mullen, whose expertise is earthquakes not hurricanes, was among the first to volunteer. As director of the university’s Center for Community Earthquake Preparedness, Mullen was equipped with two years of experience working with the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency on a statewide hazard mitigation plan for natural and man-made disasters. Using HAZUS-MH, the FEMA software, he helps planners predict damage to essential facilities before a catastrophic event.

The day before Katrina made landfall, Mullen was in Jackson, taking advisories from the National Hurricane Center and plugging the information into HAZUS. “Close to landfall, I ran the HAZUS simulation to estimate wind damage from the storm,” Mullen says. “The scale of the event was evident from our runs.”

Because HAZUS does not factor storm surge into the prediction, Mullen called on Talbot Brooks, a professor at Delta State University who specializes in geospatial data, to help with the final piece of the picture. They overlapped Brooks’ digital elevation model of the coast with the projected maximum storm surge, and Mullen then fed that information into HAZUS to predict which facilities would be affected. That news was not encouraging: Schools, highways and even an emergency operations center were determined to be directly in the surge’s path.

Many areas, such as Waveland, were predicted to be ravaged by wind even without the storm surge, Mullen says. “But combined with the seas, they got a double whammy.”

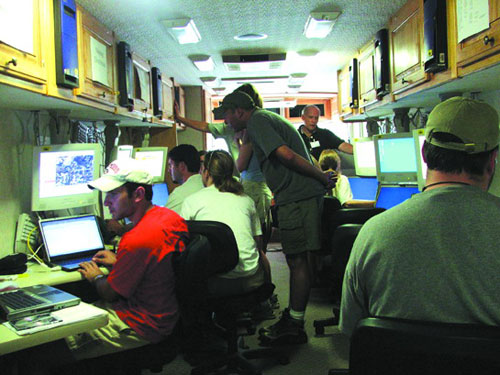

On the “GIS bus”: Graduate student Justin Janaskie (left) conducts an analysis of geospatial data as Seth Broadfoot (second from left) demonstrates GIS technology to newly arrived volunteers.

On the “GIS bus”: Graduate student Justin Janaskie (left) conducts an analysis of geospatial data as Seth Broadfoot (second from left) demonstrates GIS technology to newly arrived volunteers.

That “double whammy” spanned the entire Mississippi coast, and MEMA appealed for help.

Four days after the storm hit, a five-member UM team of geologists and geological engineers, including faculty and graduate students—all trained in geographic information systems, or GIS—set up camp at the state emergency headquarters in Jackson. Led by Greg Easson, director of UM’s Geoinformatics Center, they were armed with global positioning units, research-grade laptops and, most importantly, years of expertise in interpreting satellite data and turning it into information that rescuers and relief workers can use.

The UM team worked alongside volunteers from Mississippi State University, state and local agencies, and Giving International Service Corps volunteers in a 24-hour operation to provide GIS support to federal and state emergency response agencies.

“Our first priority when we arrived was helping the Coast Guard with search-and-rescue efforts,” Easson says. His team included graduate students Seth Broadfoot, Lance Yarbrough, Hal Robinson and Justin Janaskie.

When rescue calls came in, search-and-rescue teams were given physical addresses, but with most street signs and structures gone, there was little hope of finding exact locations. Using GIS software and a database of street names, Easson and his team provided Coast Guard helicopters with latitude and longitude coordinates of the street addresses in a matter of seconds to help them locate victims.

The team combined aerial and satellite imagery with GIS data to produce maps of the affected areas, which were used to direct rescue crews, recovery teams and law enforcement personnel to addresses that could no longer be found easily. This image, of Long Beach, shows the boundary of storm surge destruction.

The team combined aerial and satellite imagery with GIS data to produce maps of the affected areas, which were used to direct rescue crews, recovery teams and law enforcement personnel to addresses that could no longer be found easily. This image, of Long Beach, shows the boundary of storm surge destruction.

“Someone would come to us every three or four minutes,” Broadfoot said. “There were people needing dialysis, pregnant women going into labor, heart attacks. Minutes counted in those situations, so the rescue teams couldn’t wander around trying to find them.”

The GIS teams worked 12-hour shifts in an RV packed with equipment, sleeping in space provided by the State Institutions of Higher Learning.

Besides search-and-rescue efforts, they prepared detailed geospatial maps pinpointing shelters and water distribution points, closed roads, power outages, cellular coverage, aid stations, personnel locations and numerous other details. The maps were updated constantly, providing state officials, law enforcement personnel and recovery groups with details of power and cell phone service restoration, recovery efforts and locations of essential supplies.

“It’s a high-energy, high-stress environment,” Janaskie says. “But because of this experience, using GIS in emergency management really interests me as a field to go into.”

As long as a month after the hurricane struck, the UM geoinformatics team continued to work on site with MEMA. Joining the team in the meantime to relieve some of the original members were doctoral students Elizabeth Johnson and Henrique Momm.

Before and after images of Gulfport provide a striking contrast. The left photo is a QuickBird image; the right is from a NOAA post-Katrina flight.

Before and after images of Gulfport provide a striking contrast. The left photo is a QuickBird image; the right is from a NOAA post-Katrina flight.

While all have since returned to campus, their work with FEMA and MEMA continues in the cleanup, Easson says. Using satellite images with precise elevation information from before and after the storm, researchers can estimate the volume of rubble that must be cleared.

“We’re just now getting to the next huge challenge of this disaster, which is the recovery and redevelopment of the coast,” Easson says. “We believe that GIS analysis will be useful in that process as well.”

Mullen’s work isn’t over, either. He’s part of a FEMA team of structural engineers tasked with evaluating buildings in the devastated area and assessing why predictors failed to have “a better understanding of the storm’s effect on the [structural] environment on the coast.”

Responding to the worst disaster in the state’s history required state and federal agencies to rely on all kinds of outside help. Fortunately, professors, students and staff of the state’s universities were eager to help.

“It was the outstanding support we received from our universities and colleges that proved to be an invaluable asset in our ability to respond and recover from this catastrophic event,” says Robert Latham, director of MEMA.

And the UM team’s efforts may have even more far-reaching benefits, including helping officials in other states to prepare for and respond to hurricanes and other natural disasters that tax the limits of governmental preparation and response.