TThe old adage that there is strength in numbers certainly applies to a comprehensive research program. Through a network of partners, UM faculty are giving the institution a strong foundation to pursue hundreds of studies in diverse areas, ranging from particle physics and pharmacognosy to English literature and law. The scope of the university’s research endeavors is matched by the diversity of its alliances. UM scientists and scholars work with agencies at all levels of government to improve public health and safety, aid the national defense, enhance local communities and boost the economy. The efforts also involve collaborators from the private sector and peer institutions, including most of the state’s public universities and dozens more across the country. The following are a sampling of the multitude of national and international partnerships through which UM researchers are changing the world.

World Vision representatives work with the UM team to record GIS data about homes and public facilities in a village in El Salvador.

World Vision representatives work with the UM team to record GIS data about homes and public facilities in a village in El Salvador.

Preparing for natural disasters

Natural disasters are unpredictable, but new technologies are aiding emergency preparedness efforts and even make recovering from a disaster easier.

Just ask Greg Easson. For the past year, the associate professor of geology and geological engineering has been sharing equipment and data with World Vision, an international Christian relief and development agency. The collaboration has taken Easson and two of his graduate research assistants to El Salvador and Brazil, where they have demonstrated field-mapping solutions to support disaster preparedness and mitigation.

Information about and detailed maps to most locations in the United States are readily available. But gathering, processing and disseminating geographical data and demographics remain major challenges in many developing countries. El Salvador was chosen because of its exceptionally high risk for natural disasters such as hurricanes, tropical storms, mudslides and earthquakes, Easson says. The goal is to have accurate data and maps of every region in the nation.

“From previous data, we can safely predict El Salvador is inevitably going to need the information they obtain using the LumiMap technology,” Easson says. “By predetermining how many people are in what regions and what resources they have, post-disaster relief efforts should become much more effective.”

Greg Easson (second from left) demonstrates the use of a GIS hand-held recorder to enter data about key facilities.

Greg Easson (second from left) demonstrates the use of a GIS hand-held recorder to enter data about key facilities.

Before going to El Salvador, Easson and several colleagues and graduate students—all trained in geographic information systems, or GIS—helped coordinate the state’s emergency response to Hurricane Katrina. Shortly after the storm hit, the team set up camp at the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency headquarters in Jackson, where they worked alongside volunteers from other universities, state and local agencies, and GIS Corps volunteers in a 24-hour operation to provide GIS support.

Easson and his team prepared detailed geospatial maps pinpointing shelters and water-distribution points, closed roads, power outages, cellular coverage, aid stations, personnel locations and numerous other details. The maps were updated constantly, providing state officials, law enforcement personnel and recovery groups with information essential to relief efforts.

The University of Mississippi’s involvement with World Vision came about through the efforts of Henry Jones and Louise Velasquez. They are the founders of LumiMap and have donated the rights to the company name and Web site to The University of Mississippi. World Vision officials funded the team’s trip to El Salvador to demonstrate and train World Vision staff on using mobile GIS hardware and software to collect field data for World Vision’s national directors and support staff.

“World Vision is very interested in what we have to offer. Everyone there was coming up with new ways to use the Internet mapping system,” says Easson, who was accompanied by geological engineering graduate research assistants Justin Janaskie of Hot Springs, Ark., and Jasmine Karlowski of Clearwater, Fla. The system funnels GIS field data to an Internet mapping site at UM. The LumiMap/UM-hosted maps are then available for display and analysis by World Vision personnel around the world. These client maps show the latest information regarding in-country needs and resources.

A World Vision worker in El Salvador gathers information from villagers and enters it into a GIS recorder.

A World Vision worker in El Salvador gathers information from villagers and enters it into a GIS recorder.

During the initial session in March, Easson and his team combined lectures and field work to train World Vision managers on the LumiMap/UM mapping system.

“In El Salvador, we actually went out into the field and gathered the data amongst the community,” Karlowski says. “When dirt roads allowed us to travel only so far by vehicle, then we would get out and walk.”

“We went to assist World Vision in developing a GIS database of the entire country of El Salvador,” Easson says. “Using the LumiMap technology, we were successful in collecting data and making it available on the server within 12 hours.”

Shortly after the initial session, James Jones, the emergency programs officer for World Vision/Latin America and Caribbean Regional Office, invited Easson and his assistants to World Vision’s Humanitarian Emergency Affairs Regional Forum in Brazil in April. The team made presentations including a hurricane- response simulation and an online mapping demonstration and met with World Vision officials after the forum to discuss possible future collaborations. The trio also was planning an encore trip to El Salvador, where World Vision-El Salvador staff are busy creating their own survey forms and gathering data.

Graduate students Justin Janaskie (center) and Jasmine Karlowski (lower right) helped Easson train World Vision workers.

Graduate students Justin Janaskie (center) and Jasmine Karlowski (lower right) helped Easson train World Vision workers.

“All the data being collected belongs to World Vision,” Easson says. “The goal is for them to build their own, fully operational mapping operation there, but we may assist them in coordinating mapping data on the Internet.”

The UM team’s return to El Salvador was scheduled for July, during the height of the wet season, when tropical storms and rains usually cause floods and other conditions that would enable the researchers to see exactly how effective the technology and data are during a disaster.

Easson hopes to continue the partnership with World Vision and to build partnerships with other groups. In June, he presented his work on the use of technology in humanitarian emergency-response efforts at a University of Washington- hosted conference in Nairobi, Kenya.

“Since mobile GIS has the ability to greatly impact the effectiveness of disaster response, my only goal is to show these capabilities to groups that would benefit from it,” Easson says. “If these groups are unaware of the technologies that are out there, then the technology can’t be implemented. My hope is to continue working with humanitarian aid organizations.”

PROMOTING HEALTHY HEARTS

Researchers from three state institutions are following more than 5,300 African-American residents in a long-term study of heart disease that is one of the largest research projects in UM history.

The landmark study—a partnership among Jackson State University, Tougaloo College and the UM Medical Center in collaboration with several national subcontractor institutions— is investigating why African Americans nationwide, and those in Mississippi in particular, have the highest rate of cardiovascular and related diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and kidney failure. Through the research, the Jackson Heart Study plans to develop measures to prevent and treat those conditions.

The study is expected to dramatically improve the understanding, prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease in Americans, particularly African Americans. It has been funded through at least 2013 by the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Research on Minority Health and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Although much is known about the diagnosis, prevention and therapy of cardiovascular disease, “not everyone has seen the fruits of such incredible productivity,” says Dr. Herman Taylor, professor of medicine at the Medical Center and principal investigator for the JHS. (The study is an expansion of an Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study site. The ARIC study included four geographically diverse communities: Jackson, Minneapolis, Washington County, Md., and Forsyth County, N.C.)

“Cardiovascular deaths among African Americans seem to be rising while they are falling for the rest of the country,” Taylor says. “Progress has not been made in cardiovascular disease in our community for 30 or more years as compared with the rest of the nation.”

As part of the JHS partnership, the UM Medical Center is responsible for recruiting volunteers and conducting physical exams. Jackson State University has established a Coordinating Center to manage and analyze data and to coordinate community involvement. Tougaloo College has established an Undergraduate Training Center, where students take courses in public health and epidemiology and gain experience in health research.

The partnership gives Jackson, Miss., a strong investigator base for the study, which the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute expects to expand, says Dr. Teri Manolio, director of the institute’s Epidemiology and Biometry Programs.

“We wanted this to grow and really become an outstanding center for epidemiology research,” Manolio says. “This is a little different from our other epidemiology studies in that it has a very strong community component to it. It is important to bring the information back to the community. That is what we see happening in Jackson, and that is very fulfilling to us.”

When the JHS was launched in 2000, investigators recruited volunteers from across the Jackson metro area. Eighty-three percent of the 5,307 recruits came from the Jackson/ Hinds County area, 11 percent from Madison County and 6 percent from Rankin County. The group is 64 percent female and 36 percent male with an average age of 55, says Dr. Daniel Sarpong, director and senior biostatistician for the JHS.

Approximately 4,700 data points were collected on each participant, totaling more than 29 million data points, Sarpong says. Interview components included demographic information; health history; sociocultural information such as socioeconomic status, religion, stress and experiences with racism or discrimination; history of medication, alcohol and tobacco use; nutrition; physical activity; height; weight; and body size. The clinical exam component included blood pressure, electrocardiogram, carotid ultrasound, pulmonary function test, venipuncture and 24-hour spot-urine collection.

The first round of research was completed in late 2004, revealing approximately 69 percent of the JHS participants have high blood pressure and approximately a third have uncontrolled blood pressure. Extended funding for the program includes at least two more exam cycles, the first of which began last fall.

“JHS is a longitudinal study, and we’ll go through this battery of testing about every four years,” says Dr. Sonja Fuqua, JHS director of retention. “These continuing studies allow us to monitor the participants as they carry out their daily lives to see what physical and lifestyle changes may have occurred.”

The second exam includes an updated medical history and measurements of participants’ blood pressure, body-fat composition, glucose and cholesterol. Afterward, participants receive a home blood pressure monitor and instructions on taking their blood pressure.

“It’s important that participants stay the course and continue their involvement in the JHS on an individual basis so we can help them monitor their health as well as look closely at heart-disease risk factors in the African-American community,” Fuqua says.

The JHS already has yielded valuable information, Taylor says. “What we found from some of our data is if you have calcium deposits in the aortic valve, it puts you at a higher risk for heart attack and heart disease,” he says.

This finding is important because only one prior study, which focused on an older Caucasian population, suggested this might be the case, Taylor says. “I think this finding will help physicians be particularly receptive about controlling other risk factors, like blood pressure, high cholesterol or weight. I believe it was a very important finding.”

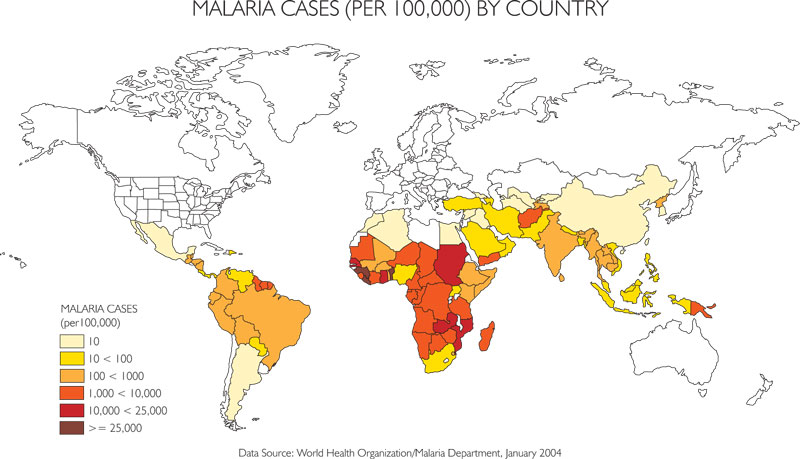

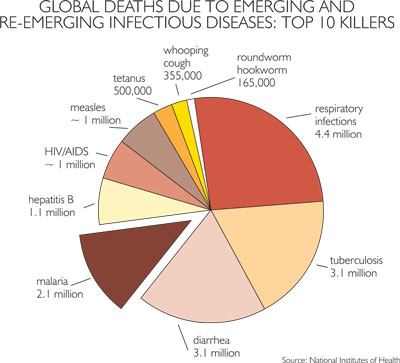

FIGHTING A TROPICAL KILLER

Unlike other ailments such as cancer and AIDS, malaria has not attracted widespread media attention or huge research efforts, despite the fact that it claims more than 2 million lives and costs billions of dollars in health care and lost productivity each year.

However, due to new funding and a string of tantalizing developments, a group of UM researchers may be poised for a major breakthrough following nearly two decades of searching for new antimalarial drugs.

This team, led by Larry Walker, director of the National Center for Natural Products Research, has studied several possible antimalarial candidates, including a promising 8- aminoquinoline called NPC1161B. (Primaquine, the drug used to treat one form of malaria, is an 8-aminoquinoline.) In laboratory tests and early animal studies, the compound appears more effective and less toxic than current malaria drugs. In the 1980s and early ’90s, several School of Pharmacy investigators worked on primaquine metabolism in research initially supported by the World Health Organization. Back then, funding for malaria was difficult to obtain. But in a serendipitous twist, a major advance for the project came when the focus expanded from malaria to AIDS complications.

“The group at Ole Miss was looking for something to help with pneumonia, which at that time was a serious problem for AIDS patients,” Walker says. It has been reported that primaquine will work against pneumocystis, a fungal pneumonia commonly reported in AIDS patients, but the drug is difficult to use and is toxic for many people.

Using funding from the National Institutes of Health, the team developed several primaquine analogs and, working with Indiana University, tested them for activity against pneumocystis. Parallel testing was conducted against malaria (at the University of Miami) and the tropical disease leishmaniasis (at the London School of Hygeine and Tropical Medicine, by the World Health Organization). One analog, called NPC1161C, showed promise against pneumocystis, malaria and leishmaniasis. NCNPR chemist Dhammika Nanayakkara, who synthesized these analogs, succeeded in separating the compound into two enantiomers, or molecules with the same composition appearing as mirror images.

“The more we tested, the better these compounds looked as potential antimalarials,” Walker says. One of these enantiomers—1161A— demonstrated better activity against malaria than primaquine but proved too toxic. The other—1161B—is more effective and less toxic than 1161A.

Since malaria has been nearly nonexistent in the U.S. for decades, development money for new antimalarials is scarce. So, in the ’90s, Walker’s team, working with ElSohly Laboratories Inc., landed modest grants from the NIH to continue basic scientific work on synthesizing and testing the compounds.

A breakthrough came in late 1999, with the creation of the Swiss-based Medicines for Malaria Venture, a nonprofit foundation dedicated to developing affordable new antimalarials. The group solicited proposals from international researchers and chose several— including two from UM—for funding in 2003. One of those was NPC1161B.

“One of the reasons MMV picked our compound for further study is that they have several projects in their portfolio that target malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum,” Walker says. “But the second- most common form of malaria is Plasmodium vivax, which has a different impact on patients and has to be treated with a different set of therapies.”

P. falciparum is the most severe form of malaria and can be fatal. P. vivax is not as severe physically but is economically devastating because symptoms last much longer.

Besides showing promise against P. vivax, 1161B also may be useful against P. falciparum and may provide an alternative to chloroquine, one of the oldest malaria drugs. In countries where malaria is a major health problem, chloroquine resistance is growing dramatically. While much work remains, Walker is optimistic the compound may become the first new drug to treat P. vivax in more than 50 years.

“The discovery and development of new drugs is a demanding, expensive, high-risk endeavor,” Walker says. “It is very gratifying that, after the research efforts of dozens of people over two decades, we can see the real possibility of a major new treatment for the millions of people who suffer from malaria.”

JOINING THE AVIATION AGE

Barely two years after helping develop a framework for civil aviation regulations in Mongolia, law professor Jacqueline Serrao has taken on a challenging project in the African nation of Mozambique. Serrao is developing a complete set of aviation laws for the nation, including regulations for airport licensing and certification.

A licensed pilot and associate director of the UM National Remote Sensing and Space Law Center, she was selected for the project by the World Bank and Mozambique government. Through a World Bank grant, Serrao also is developing the organizational structure and staffing for a Mozambique Civil Aviation Authority division responsible for aerodrome (small airport) standards and safety.

Jacqueline Serrao

Jacqueline Serrao

“This is quite a challenging and exciting project,” Serrao says. “It involves creating a set of airport laws and regulations suited to the aviation market of Mozambique while maintaining international U.N. standards. I’ve had to quickly grasp Mozambique’s legal, social, political and economic structure and fit that into a comprehensive body of aviation law.”

Serrao has extensive experience in international aviation law, having served as an international aviationoperations specialist at the FAA’s Office of International Aviation, where she was responsible for creating and analyzing international FAA policies.

Located in southern Africa, Mozambique is one of the world’s poorest countries. It was embroiled in a 16-year civil war until 1992, but since then, governments have worked to restore order and grow the economy.

According to the U.S. State Department, “As there is no direct commercial air service between the United States and Mozambique, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration has not assessed Mozambique’s Civil Aviation Authority for compliance with International Civil Aviation Organization international aviation safety standards.” However, Serrao’s work could help bring the country into compliance with international safety standards for airports—the first step in opening up airspace to more international air traffic and bringing the country up to ICAO standards.

“A country’s aviation system is only as safe as its government’s ability to oversee that system,” Serrao says. “In this case, airport legislation is necessary to ensure that the Mozambique Civil Aviation Authority can effectively carry out its aviation- safety oversight responsibilities. Without such a commitment to aviation safety, investors will be reluctant to enter the Mozambique market. A country that does not have a legal infrastructure in place tends to get left out.”

Serrao traveled to Mozambique in October to evaluate the aviation law and regulatory regime and to begin drafting the country’s airport regulations. Her evaluation revealed that the country has a “patchwork” of laws of different weight and authority, some dating back to the mid-1920s. She is collaborating with a Mozambique attorney, who has been briefing her on his country’s constitution, labor code and administrative laws.

While in Mozambique, Serrao was invited by the country’s Civil Aviation Authority to present a twohour lecture on air and space law at the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane. This was the first time that a lecture on the subject had been presented in Mozambique, and the session was attended by the university’s dean of law, law professors and about 150 law students.

Serrao’s aviation-law expertise is recognized in many places around the world, says Joanne Gabrynowicz, director of the UM space law center. “She’s doing important work that is bringing international attention to The University of Mississippi.”

Serrao has logged thousands of miles in her efforts to help build a legal framework for civil aviation in Africa.

Serrao has logged thousands of miles in her efforts to help build a legal framework for civil aviation in Africa.