Stemming A Violent Tide

anti-sniper detection better structures blast-resistant material computer simulations engineering identification impact improvised explosive device land mines laser doppler vibrometer lasers mirrors nanotechnology physical acoustics pinpointing technology retrofitting robust designs sound waves the university of mississippi

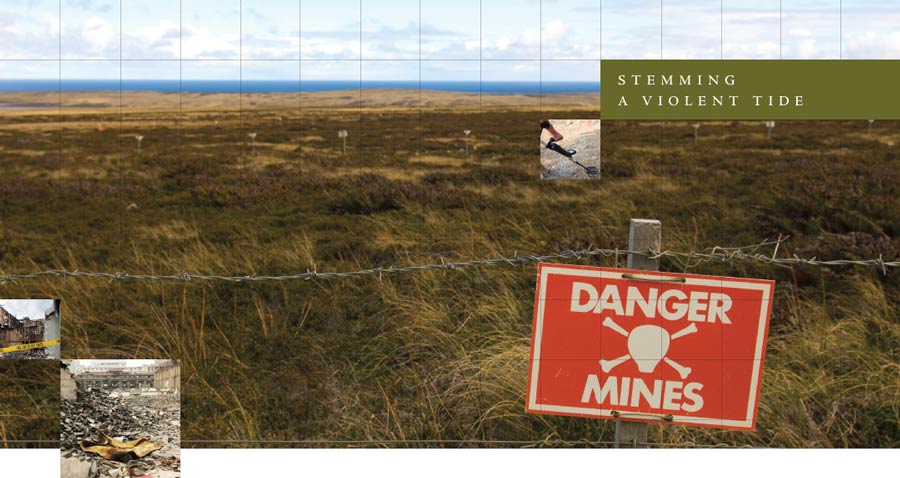

University of Mississippi researchers work to make this violent world a little safer with technologies that detect land mines more efficiently than before, can tell the difference between a nuclear test or a little dynamite in North Korea, pinpoint a sniper or an improvised explosive device, or retrofit buildings into armored fortresses.

Protecting the Innocent

In the throes of battle, fields are seeded with land mines aimed at picking off soldiers. But many are never triggered, lying underground for years until they are set off by an innocent person—a child playing or a farmer plowing a field.

An estimated 80 million land mines are buried in 88 countries around the world, from Mozambique to France (where bombs from both World Wars are occasionally triggered). Thousands are killed or maimed every month.

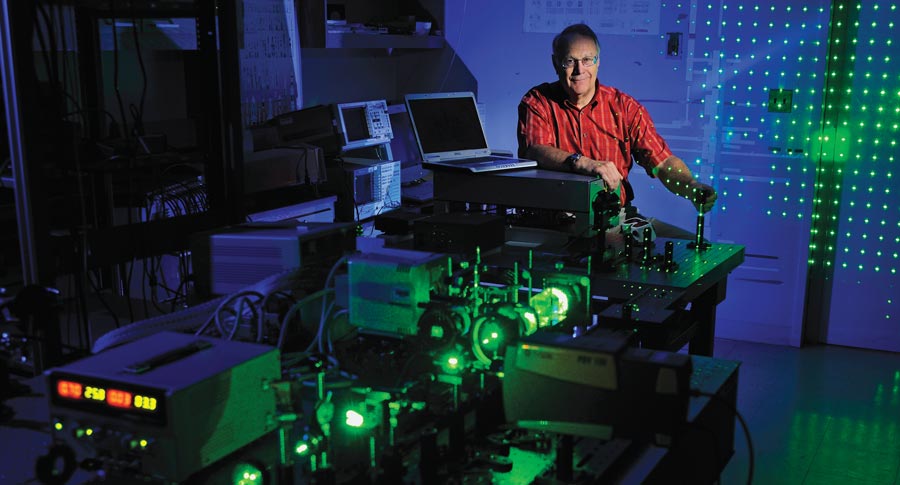

Some of the top physicists in the world work for Ole Miss, many at the groundbreaking National Center for Physical Acoustics (NCPA). One of them, Dr. Jim Sabatier, developed the multibeam laser Doppler vibrometer, which allows scientists to see through dirt using sound waves. On the screen, land mines appear as hot red blobs, much easier to detect and remove than with traditional techniques like metal detectors, which can’t see plastic, or ground-penetrating radar, which doesn’t work in wet soil or other adverse conditions.

The first version of the laser Doppler vibrometer sprawls across a table in a lab at NCPA, a chain of lasers and mirrors that look like lines of dominoes. The next version fits into a big, bulky, heavy metal box. The latest, more accurate than the first, is contained in a heavy—but much, much smaller—box.

The device is much more accurate than any land mine detection tactic used before, clearing fields with a 99.7 percent accuracy, called “unmatched” by the U.S. Army. The success of the device led to the establishment of the Institute for Humanitarian Demining, which aims to constantly improve the detection system, look for new solutions and use a multidisciplinary approach to address all the problems associated with the use of land mines.

Battlefield Ready

NCPA is a designated Army Center of Excellence in Acoustics, providing the Army with a continuous source of expertise and innovation.

One such innovation is applying NCPA’s land mine detection technology to locate improvised explosive devices before they explode. This adaptation of the proven system is more complex than it sounds. To find a land mine, the detection device points straight down through soil in a static environment. But an IED is not buried, it is just hidden. Identification must be instantaneous for the soldiers in the field.

“Using the same technology to scan for explosives at some distance and beside the device presents a number of challenges that will take more research to overcome,” Sabatier said. “There’s more distortion beaming to the side rather than straight down. At the same time, the scan has to be done much more quickly. so we have a lot of work to do.”

An anti-sniper detection system is already being used on the ground in Iraq.

“The combination of rugged wireless microphones and GPS has the potential to instantly pinpoint a sniper’s location,” said Dr. Kenneth Gilbert, the lead researcher on the project. “The NCPA atmospheric research group is actively working on making such a system a reality.”

Armor For Bricks And Mortar

Advances in body armor save the lives of soldiers every day. A research team in the School of Engineering aims to do the same for buildings using nanotechnology.

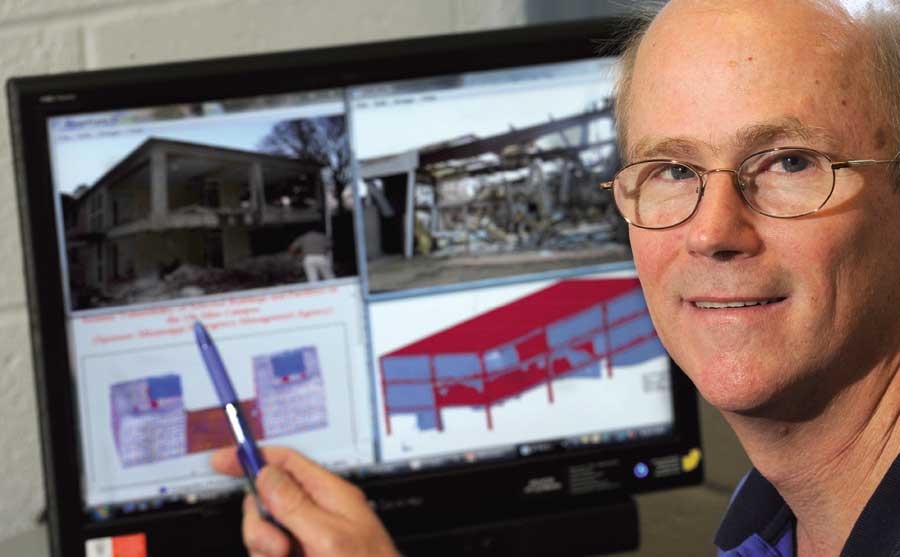

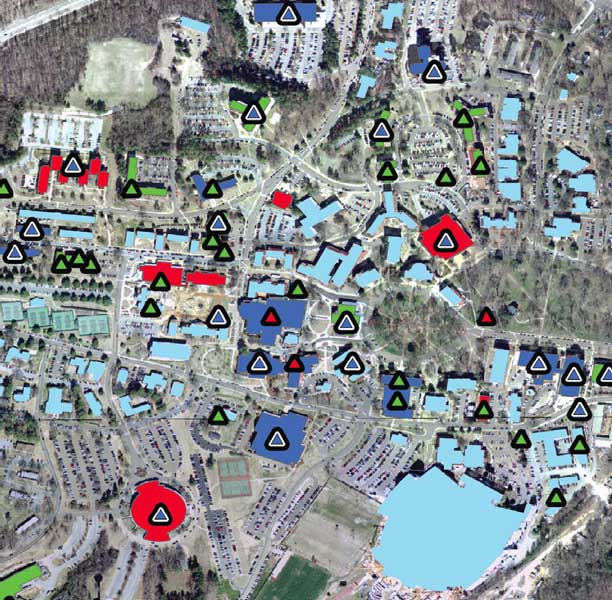

Dr. Chris Mullen, a civil engineering professor who is also the director of the Center for Community Earthquake Preparedness, developed a computer model that simulated the effects earthquakes of different magnitudes would have on buildings—first for a campus project, and then for the federal and state emergency management agencies.

Using that model as a jumping-off point, Mullen and his civil and mechanical engineering colleagues are trying to mitigate the effects of a terrorist blast on buildings in a project funded by the Department of Homeland Security. Mullen’s model simulates the impact of a blast on a building that is not protected first. Then the team calculates the impact after the building is retrofitted with a cost effective, blast-resistant nanoparticle-reinforced material.

Mechanical engineering professors Dr. Ahmed Al-Ostaz and Dr. P.R. Mantena are working to design the blast-resistant material at the nano level. The materials team then must work out how best to apply it, Mullen said. Should they make it a spray paint? adhesive strips? a large-scale flexible wallpaper?

After choosing how best to apply the protectant, the team will use computer simulations to decide how to retrofit an entire building.

“The blast simulation indicates which part of the building will fail—the distribution of the damage,” Mullen said. Based on those results, the team can develop retrofitting strategies for Homeland Security.

Although the Homeland Security project doesn’t have anything to do with earthquakes, the work Mullen is known for, he says this new direction really isn’t that different.

“Earthquakes do pretty wicked stuff to buildings in a different way,” Mullen said. “With better structures and more robust designs, buildings can be multi-hazard-proof—whether it’s a terrorist blast, an earthquake or a hurricane. It’s all related.”