Reaching Out Around The Globe

Aid Airport Licensing Aviation Laws Computational Hydroscience Dams Developing World Disaster Preparedness Disease Emergency Response Emerging Resistance Erosion Field Mapping Geographic Information System Infection International Safety Standards Malaria New Drugs Relief Supplies Distribution Remote Sensing Space Law Water Quality The University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi researchers are affecting the lives of people thousands of miles from Oxford, Mississippi, with their research on drugs, remote sensing, space law and computational hydroscience.

Stopping A Killer

More than 2,000 people die every day from malaria. Most of those deaths—about 90 percent—are children. Many millions more are infected every year with the disease, which ravages the body, making it impossible to work or take care of a family.

If this debilitating killer ravaged Ohio or Ontario or Great Britain, malaria would be the focus of every drug company research and development lab in the country. But most of these cases affect people in Africa or Southeast Asia—impoverished people who can’t buy medicine.

That meant that, until recently, drug researchers such as Dr. Larry Walker and his colleagues couldn’t get the research funding they needed to fight the disease.

That began to change for Walker, the director of the University of Mississippi’s National Center for Natural Products Research, in 2003. Swiss-based Medicines for Malaria Venture, a nonprofit foundation dedicated to developing affordable new anti-malarial drugs, solicited proposals from international researchers and chose to fund several—including two from UM’s School of Pharmacy, one of the premier natural products research programs in the country.

“It’s a huge undertaking,” Walker said. “We’re just getting started.”

Just getting started—except that the University of Mississippi group has been pursuing anti-malarial compounds for two decades now.

“For the most standard anti-malarial drugs, the problem is emerging resistance,” Walker said. “That means we always need new drugs to fight the disease.

“The other major problem with anti-malarial drugs is that many of them have safety problems,” Walker said. “A small but significant number of people can become very sick or even die from them.”

The most promising new drug, an 8-aminoquinoline called NPC1161B, was prepared by Dr. Dhammika Nanayakkara, a chemist at the university’s National Center for Natural Products Research. It was advanced during the 1990s by a team of researchers, including Dr. Alice Clark, current vice chancellor for research and sponsored programs, who were searching for cures for infections in AIDS patients. When Walker joined this project, his main focus was on how the drug might work in animals. NPC1161B appeared much less toxic and much more effective than products on the market in lab tests and animal studies. The next step is human testing, which is anticipated to begin next year, Walker said. If that goes well, the drug could be on the market in three years. Still, “the failure rate is pretty high,” Walker said, but the team is optimistic.

“We’re not looking to realize monetary gains on this. That wasn’t the point,” Walker said. “We want to contribute to the effort to eradicate this disease for good.”

Mapping For The Worst

After a hurricane, it’s hard enough for emergency responders in the United States to locate the people who need help and provide them with adequate shelter. And we have a distinct advantage over the developing world: maps, street maps and grids, the trappings of a highly organized structure that helps us find where we’re going, locate resources and get them to those in need.

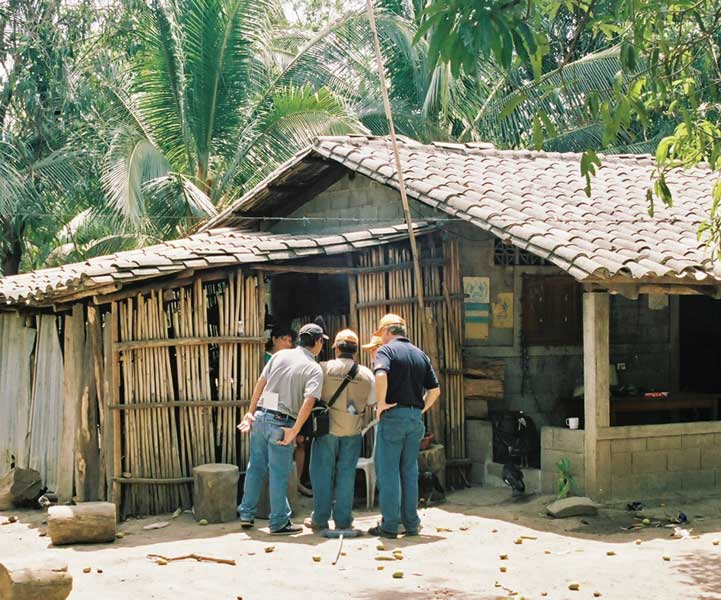

Put those emergency responders in a remote village in El Salvador, which has no street names and no record of who lives where. In a disaster, what do you do? How do you begin to help?

Geology and geological engineering associate professor Dr. Greg Easson and his group, LumiMap-UM, are partnering with World Vision, an international aid organization and development agency, to develop and demonstrate technological solutions for field mapping to aid in disaster-preparedness projects.

The team first visited El Salvador because of its exceptionally high risk for natural disasters such as hurricanes, tropical storms, mudslides and earthquakes, Easson said. World Vision in El Salvador was the lead partner for World Vision, and their goal is to have up-to-date information about the population, especially those people living at the margins of villages, often in small shacks on land they do not own. These data will help World Vision in El Salvador develop more effective plans for shelters during a disaster and determine what supplies are needed to speed the recovery.

“By predetermining how many people are in what regions and what resources they have, post-disaster relief efforts should become much more effective,” Easson said.

Here’s how it works: After being trained by LumiMap-UM staff, World Vision staff and community workers set out to every corner of El Salvador carrying hand-held computers with Global Positioning Systems (GPS). The workers use the mobile Geographic Information System (GIS) to enter the survey information into the hand-held device, which instantly records their location with the GPS.

The system funnels the field data to GIS database, which manages the data for an internet mapping site at UM. The LumiMap-UM-hosted Web site makes the maps available for display and analysis by World Vision personnel around the world. These maps can be used to plan for effective distribution of relief supplies.

“In El Salvador, we actually went out into the field and gathered the data amongst the community,” said Justin Janaskie, one of the graduate students who accompanied Easson. “When dirt roads allowed us to travel only so far by vehicle, then we would get out and walk.”

Easson said after the initial surveys in El Salvador, data were available via LumiMap-UM server in 12 hours. Since then, Easson has taken the same project to Brazil, back to El Salvador and to Mexico in the summer of 2008. He hopes to continue to work with World Vision International to more fully incorporate the use of mobile GIS into their development and disaster-response efforts.

Easson and his staff have presented their work on the use of technology in humanitarian emergency response efforts at a conference in Nairobi, Kenya, at local civic groups and in a special session of the ESRI user conference in San Diego, California.

Transferring Knowledge

The National Center for Computational Hydroscience and Engineering (NCCHE) has been invited by the United Nations, the Interamerican Development Bank and by foreign governments, supported by USAID, to transfer its technology in order to help developing countries.

NCCHE is led by Sam Wang, a fixture of UM engineering for 40 years. Wang is recognized worldwide for his work building computational models that not merely estimate but actually simulate water flows, sediment and pollutant transport, soil erosion and flood damage.

Wang has won the world’s highest honors in erosion and sedimentation research: the Hans Albert Einstein Award in 2003 and the WASER Qian Lin Award in 2007.

Although most any graduate student with a grant can build a computational model, NCCHE’s model has benefited from years of adjustments made by dozens of expert researchers.

“The quickly executed model can solve one or two problems in the proposal, but once the student graduates, there is nobody to improve it,” Wang said. “As a result it becomes obsolete. Our institution is different. We develop the model collectively, and we continuously improve by updating with the latest technology, even in theory or mathematical methodology. If something new is happening, we immediately try to put that in our model. Therefore our model always stays at the forefront.”

Wang has given keynote speeches, special lectures and instructional courses in more than 30 countries on six continents. At the center of Wang’s globetrotting: sharing his groundbreaking computational models with the developing world so that better dams can be built, water quality can be controlled and erosion can be mitigated—basically, so that life can become better for millions of people.

This kind of technology transfer operates on the “teach a man to fish” philosophy.

“The most effective assistance given to a developing country is transferring the technology to them so that they can solve their own problems, ” Wang said, “instead of outsiders’ building something for them.”

Fly Mozambique? It Starts In Mississippi

Whether they want to regulate their airports or observe earth from outer space, many nations invite the National Center for Remote Sensing, Air and Space Law to help them. Without the work of the center, international airports could not operate. Satellites could not be deployed. Chaos would reign in aerospace and outer space. The center, with its worldwide and otherworldly focus, is based here at Ole Miss.

“If you’re a nation that’s just starting to get involved in space law, and you are looking for expertise, you talk to people like us,” said Joanne Gabrynowicz, the director of the National Center for Remote Sensing, Air and Space Law. “The United Nations Office on Outer Space Affairs conducts space law capacity-building workshops in a different country every year. The U.N. office brings together scholars from around the world—often, that’s us—and sends us to each of these countries in order for the decision makers in those countries to talk to us about what they need to do.”

Some of the nations that consult with Gabrynowicz and her staff do want to build space programs. But some of them want something simpler—like an international airport to jump-start trade and tourism. To do that, a nation needs a complete set of aviation laws—so they turn to the center.

Barely two years after helping develop a framework for civil aviation regulations in Mongolia, the center’s associate director, Jacqueline Serrao, has taken on a challenging project in the African nation of Mozambique. Serrao is developing a complete set of aviation laws for the nation, including regulations for airport licensing and certification.

Through a World Bank grant, Serrao also is developing the organizational structure and staffing for a Mozambique Civil Aviation Authority division responsible for aerodrome (small airport) standards and safety.

“This is quite a challenging and exciting project,” Serrao said. “It involves creating a set of airport laws and regulations suited to the aviation market of Mozambique while maintaining international U.N. standards. I’ve had to quickly grasp Mozambique’s legal, social, political and economic structure, and fit that into a comprehensive body of aviation law.”

Located in southern Africa, Mozambique is one of the world’s poorest countries. Embroiled in a 16-year civil war until 1992, the country has since worked to restore order and grow the economy with the help of some foreign aid.

Serrao’s work could help bring the country into compliance with international safety standards for airports—the first step in opening up airspace to more international air traffic.

“A country’s aviation system is only as safe as its government’s ability to oversee that system,” Serrao says. “In this case, airport legislation is necessary to ensure that the Mozambique civil aviation authority can effectively carry out its aviation safety oversight responsibilities. Without such a commitment to aviation safety, investors will be reluctant to enter the Mozambique market. A country that does not have a legal infrastructure in place tends to get left out.”